The Atacama Desert on the Chilean high plateau of Altiplano and the Mauna Kea Summit on the Big Island of Hawaii are generally recognized as the two best places for astronomical observations. However, in this article, I argue that the best place for amateur night sky photography is elsewhere. It is in Hawaii too, but on the Island of Maui. It is the extinct Haleakala volcano. Although smaller than the Mauna Kea volcano, Haleakala might actually be better suited for amateur photographers.

Milky Way and the observatories at the summit of Haleakala volcano

NIKON D750 + 20mm f/1.8 @ 20mm, ISO 6400, 15/1, f/2.5

The combination of dark sky (due to the absence of light pollution) and high altitude with little cloud is what makes the Atacama Desert on the Chile-Bolivian border and Mauna Kea Summit so unique. It is therefore no wonder that one finds state-of-the-art technology telescopes in those sites: in Atacama, the ALMA project as the world’s largest system of 66 telescopes was launched in 2013; Mauna Kea Summit is the second largest observatory for optical, infrared and submillimeter astronomy. I have had the great fortune to have visited both these locations (I was not at the ALMA site itself, as it was under construction back in early 2013, but I went to a public observatory nearby). And that is why I dare pronounce this verdict: those sites are great for experts working for those observatories, but not so great for amateur photographers.

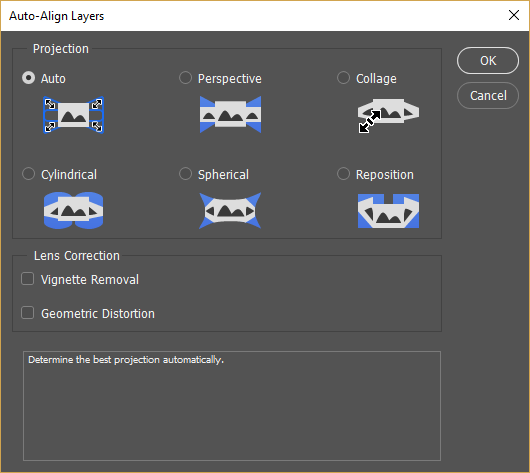

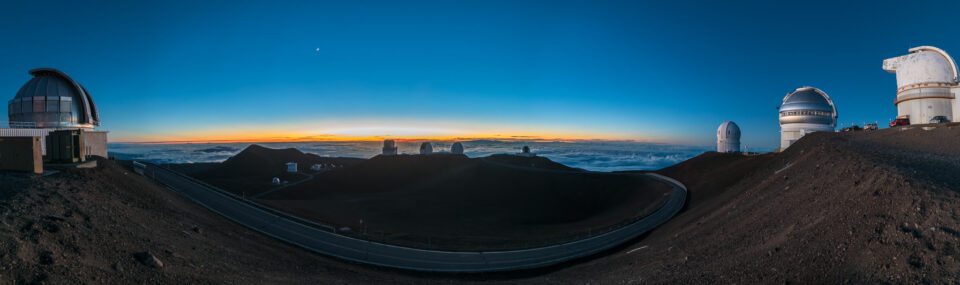

Panorama of Mauna Kea Summit with observatories

NIKON D750 + 14mm f/2.8 @ 14mm, ISO 100, 8/10, f/4.5

Don’t get me wrong, I am not arguing that the Atacama Desert and Mauna Kea Summit are not unique and beautiful enough. They absolutely are and you should visit them, not only because of the dark sky.

Summit of Mauna Kea with telescopes and the Summit of Mauna Loa on the top left corner

NIKON D7100 + 10-24mm f/3.5-4.5 @ 13mm, ISO 100, 1/100, f/8.0

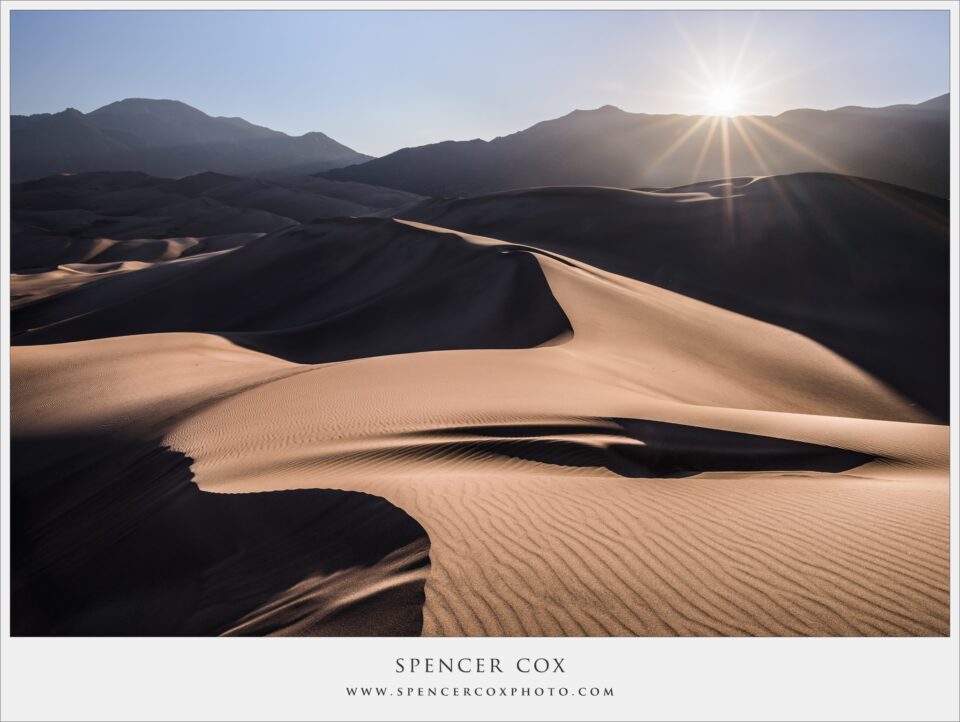

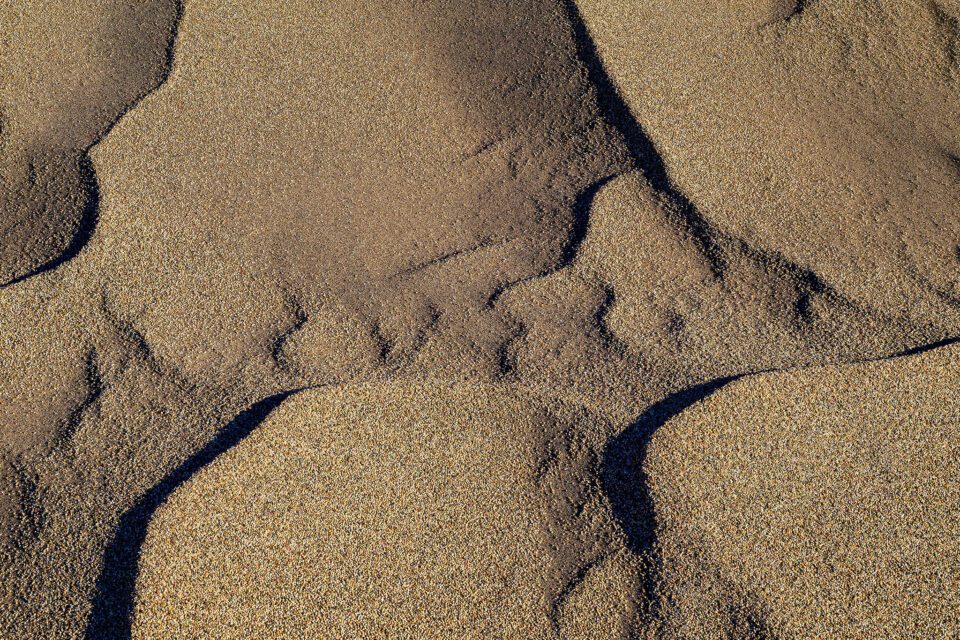

Altiplano landscape and the Atacama Desert are stunning and a true paradise for landscape photographers

NIKON D7000 + 10-24mm f/3.5-4.5 @ 17mm, ISO 100, 1/500, f/6.3

However, if your interest is primarily astrophotography, you should know that taking those incredible Milky Way shots there is not so easy. Why?

Both the Atacama Desert and Mauna Kea observatories lie well above 4 000 m (12 000 feet). For that reason, you need to acclimatize yourself and even then you might still suffer from altitude sickness. But that is by far not the main hassle. Unfortunately, there are further restrictions. Mauna Kea Summit is open to the public, but only from dawn to dusk, when the telescopes are inactive. Staying overnight is forbidden, unless you have a special permit. I found out that it takes a year or even longer for professional photographers with long records in astrophotography to obtain such a permit.

The summit of Mauna Kea can be reached by a standard car, but due to a gravel-road part it is highly recommended to take off-road car

NIKON D7100 + 70-200mm f/4 @ 130mm, ISO 100, 1/200, f/9.0

Shortly after sunset you must leave the Mauna Kea Summit

NIKON D7100 + 10-24mm f/3.5-4.5 @ 20mm, ISO 100, 1/25, f/4.5

Moreover, tourists need to hire an off-road vehicle, since the upper part of the route is on a steep gravel road (actually, I encountered some normal cars too, although most standard hired cars are not insured for the Mauna Kea Summit trip). Anyway, regardless of the type of your vehicle, shortly after sunset, you are kindly but firmly informed by a ranger to leave the summit.

Nightsky with Milky Way shot near the Onizuka Center observatory. Sometimes, the headlights of passing car can lit the landscape in a very nice way, but most of the times, you can get frustrated by too much light coming out of them

NIKON D750 + 14mm f/2.8 @ 14mm, ISO 4000, 30/1, f/2.8

Photographing below the summit is possible and definitely worthwhile, but since there is an observatory running star-gazing programs that have become very popular, you will encounter crowds and ceaseless traffic. Car headlights can thwart any of your dark-sky shots at any time. I found this very distracting when shooting below Mauna Kea.

I was unlucky when shooting night sky near San Pedro de Atacama – moon was already in the third phase and there were clouds, which happens allegedly only a few times per year

NIKON D7000 + 11-16mm f/2.8 @ 11mm, ISO 1000, 30/1, f/3.5

Shooting in the Atacama Desert is difficult in other aspects. The Atacama Desert is vast and, unlike at Mauna Kea, there is no problem in finding a dark spot to shoot from without any permit. You might have to travel long distances to find an interesting foreground for a good composition. The vastness also makes it a bit dangerous (especially the high-altitude Atacama Desert near the Argentina-Bolivian border) when far from larger cities – the closest town being San Pedro de Atacama. Many surrounding areas do not have any GSM coverage. Running out of gas or water might be a big problem. Furthermore, for a reason I could not understand, when traveling into and out of the town of San Pedro de Atacama, one has to pass through something like Customs control every single time – which can be a very lengthy and rather unpleasant procedure for those who have not mastered the Spanish language.

That is why I find Haleakala Summit on the Hawaiian Island of Maui to be a much more convenient site for amateur photographers. Here are the exact reasons why:

- The conditions for great night photos are no less perfect; you still get the great combination of dark sky and high altitude.

- There is zero light pollution to the east and south, very little pollution to the west and north.

- Interesting foregrounds are to be found in all directions. There are two parking lots. The lower one is located near the Visitors’ Center, which has a perfect viewpoint to the east over the Haleakala Crater. Here you may take perfect compositions in early March and April. At the very top, there is one more parking lot with another summit building. From here, you can see the observatories to the south. These function primarily during the day, so restrictions here are not so strict and it is possible to get closer to the telescopes and have them in the foreground. They are perfect for compositions from May to September. Moreover, at the parking place, there are many silversword plants that also fit nicely as foreground.

- Haleakala Summit is easy to access on an asphalt paved road, an off-road vehicle is not needed. There is no problem with the insurance of hired cars, unlike in the case of ascending Mauna Kea.

- You are 54 km (33.5 miles) away from the sea (and what a beautiful one) and the city of Kahului with all the services, restaurants, shops. There is also a very limited capacity of accommodation in the hotels and motels along the Haleakala road.

- Even if you get up to 3 055 meters (10 023 feet) above sea level, which is high enough for crisp air, you will most likely not suffer from high-altitude sickness.

- At night, there are no crowds; I saw some cars with organized groups but they were gone after 11 p.m. There are no rangers, no controls.

- No special permit to stay overnight is needed; you only have to pay the entrance fee of 15 USD (valid for 3 days) to the Haleakala National Park.

- It is possible to stay overnight. There are rough and ready conditions in the Visitors’ Center booths at the summit – you need to have your own mattress and a warm sleeping bag. A few miles below the summit, you can sleep in a tent in the Hosmer Grove Campground (no permit needed, on a first-come, first-served basis).

- If you stay overnight at the summit, you get a very spectacular Haleakala Crater sunrise from the lower Visitors’ Center as a bonus.

- Maui offers even more locations for good night photography; theoretically you can shoot the Milky Way both from the seaside and the volcano summit in one night.

But I should also warn you, even here the conditions may get very rough:

- It is usually very windy up there; keeping my tripod stable in a gale-force wind was the biggest challenge for me.

- Needless to say, it gets bitterly cold overnight (freezing temperatures even in summer). Wearing many warm layers of good clothing is crucial.

- Even if the road is in top quality, it is still a demanding drive – driving the 54-km (33.5-mile) route from Kahului with all the bends takes at least 1.5 hours.

- The night may not be completely cloudless. The middle layer of clouds is usually below the highest peak, yet there are nights with high clouds (around 10 km / 6 miles), so there is no guarantee of perfect weather (you do not get this at Mauna Kea or the Atacama Desert either).

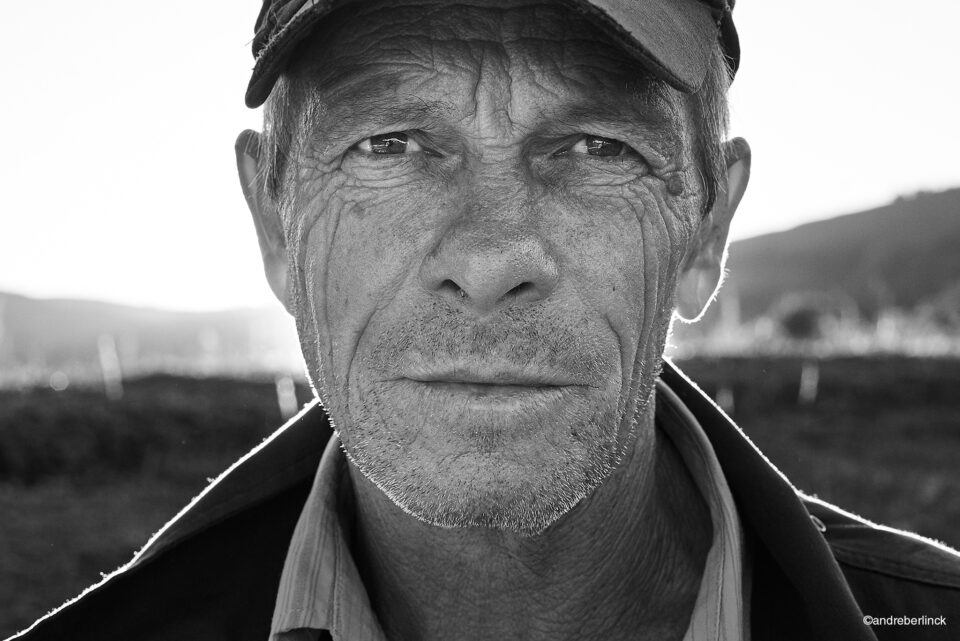

Self-portrait – I was lucky that a thin layer of clouds was passing over the summit exactly at the right time – otherwise the light from my head torch would not be visible

NIKON D750 + 20mm f/1.8 @ 20mm, ISO 10000, 15/1, f/2.5

Last but not least, let me point out that I do not want to tell you guys that, in order to get great astrophotography images, you have to go to Haleakala Summit.

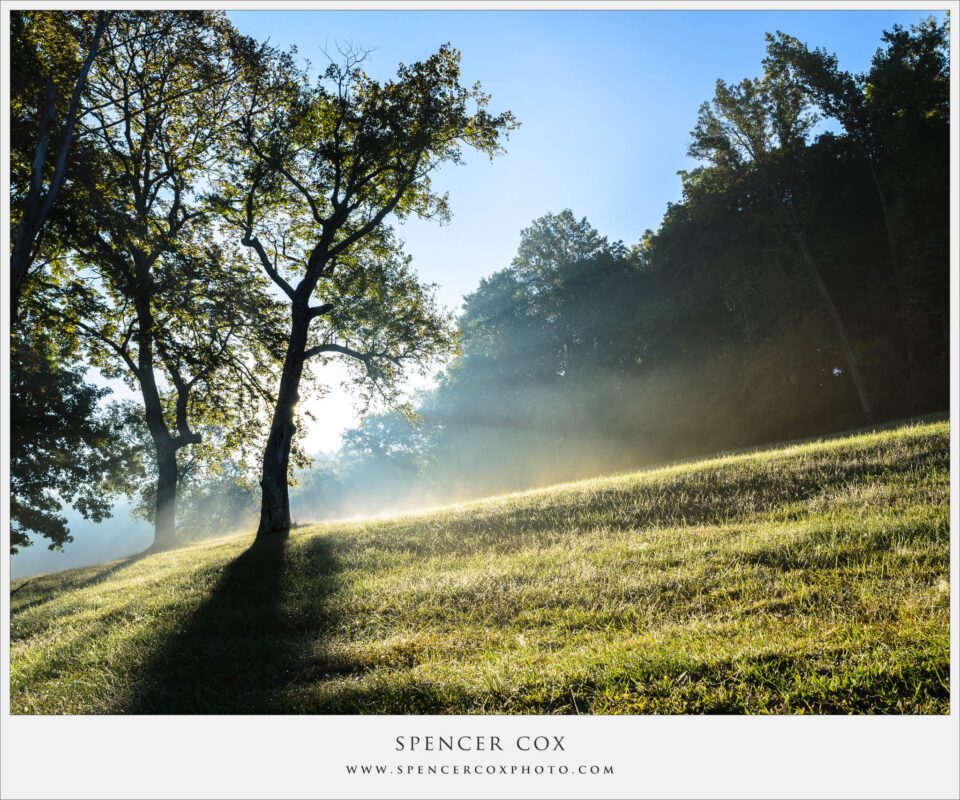

I took this shot in Ondrejov Observatory barely 20km away from Prague – the darkness of the sky is nowhere to be compared with Hawaii and yet I got a decent image

NIKON D750 + 14mm f/2.8 @ 14mm, ISO 3200, 30/1, f/2.8

I enjoy shooting night images in the Bohemian Paradise in Central Europe, where there is a moderate to high level of light pollution according to this map. The conditions are incomparably worse there, yet I immensely enjoy the process of taking the photos. But if night photography becomes your passion or even obsession (as it is in my case), Haleakala Summit in Maui should be on your bucket list.

This guest post was submitted by Vaclav Bacovsky, a photographer from the Czech Republic (in the very heart of Europe). He loves shooting landscapes, architecture, macro and wildlife (see his 500px page). He blogs at www.krasnesvetlo.cz (in Czech language only though). And his infrared photographs are published on his Instagram account.

The post The Best Place in the World for Amateur Night Sky Photographers appeared first on Photography Life.

from Photography Life https://photographylife.com/the-best-place-in-the-world-for-amateur-night-sky-photographers